Why Getting Everything You Want Makes You Miserable

The paradox of plenty: why progress makes life feel emptier, not fuller

The Mall at 3 AM

Picture this: You're standing in an abandoned shopping mall at 3 AM. The escalators still hum. The fountain still bubbles. Every store window gleams with perfect products nobody needs.

This is what progress feels like in 2025. We built the infrastructure for happiness, stocked every shelf with solutions, automated every inconvenience. Yet here we are, wandering the corridors at odd hours, feeling more lost than our ancestors who had nothing.

Three thinkers saw this coming. Two of them are dead. One framework is just being born.

The Problem Nobody Wants to Name

We've solved more problems in the last century than in all of human history combined. Infant mortality plummeted. Information became infinite. Connection became instant.

So why does a Harvard study show that 36% of Americans feel "serious loneliness"? Why do we have a mental health crisis in the most prosperous nations? Why does each career milestone feel smaller than the last?

The uncomfortable truth: progress itself might be the trap.

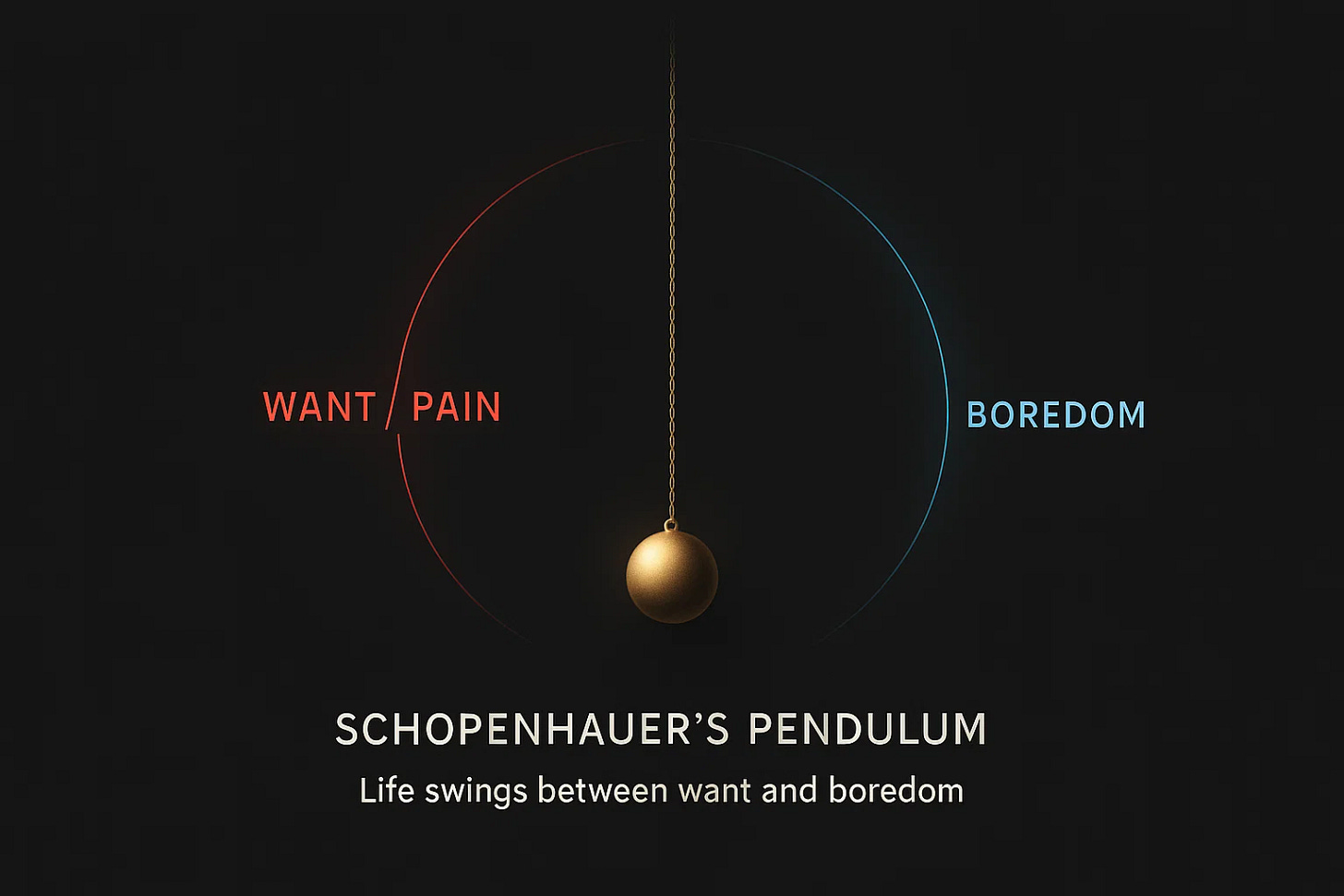

Schopenhauer: The First Diagnosis

Arthur Schopenhauer figured this out while Napoleon was still marching around Europe. His insight was brutally simple: humans are cursed with an endless "will to live" that can never be satisfied.

Want food? You eat, feel briefly full, then hunger returns. Want love? You find it, feel complete, then anxiety creeps back. Want success? You achieve it, feel victorious for a week, then the goalposts move.

Schopenhauer called this the pendulum of existence — we swing between want (suffering) and satisfaction (boredom). There's no stable middle ground. The will keeps willing, even when there's nothing left to will toward.

His solution was radical withdrawal. Stop wanting through aesthetic contemplation (lose yourself in art) or ascetic denial (become a monk). Basically, opt out of the game entirely.

Problem is, most of us have mortgages.

Cioran: The Mood of Exhaustion

Emil Cioran took Schopenhauer's diagnosis and marinated it in twentieth-century disillusionment. Where Schopenhauer was systematic, Cioran was symphonic — he didn't argue points, he evoked moods.

"We are all geniuses when we dream," he wrote, "the butcher then is a poet." But civilization? That's where dreams go to die. Every institution becomes a fossil. Every revolution becomes bureaucracy. Every utopia becomes a parking lot.

Cioran didn't offer solutions because he didn't believe in them. Progress was a cosmic joke, and the punchline was that we kept falling for it. His aphorisms read like messages from someone who's seen the end of every story: "The fact that life has no meaning is a reason to live — moreover, the only one."

Where Schopenhauer prescribed withdrawal, Cioran prescribed... nothing. Just the lucid recognition that we're trapped in an exhausted culture, producing exhausted thoughts, in an exhausted cosmos.

Cheerful guy.

Ward's Paradox: The Pattern Finally Has a Name

Here's where Ward's Paradox enters, not as philosophy but as observable mechanics. It's not about withdrawal or resignation. It's about understanding the specific mechanisms that turn progress into dissatisfaction.

Ward's Paradox identifies three interlocking processes:

1. Goal Escalation: Success redefines the baseline. A promotion doesn't make you successful; it makes you someone who needs a bigger promotion. Dating apps don't solve loneliness; they create infinite options that make commitment feel like settling.

2. Loss of Unifying Struggle: Comfort eliminates the shared challenges that create meaning. Our grandparents had the Depression and World War II — terrible, but unifying. We have Twitter arguments about pronouns. The stakes feel both overwhelming and utterly trivial.

3. Integration Failure: We optimize parts without integrating wholes. Your career might be thriving while your marriage collapses. Your city might be economically booming while community dissolves. We're winning all the games while losing the meta-game.

Unlike philosophical moods, these mechanisms are measurable. You can track goal escalation in salary expectations. You can measure integration failure in burnout rates. You can see loss of unifying struggle in political polarization.

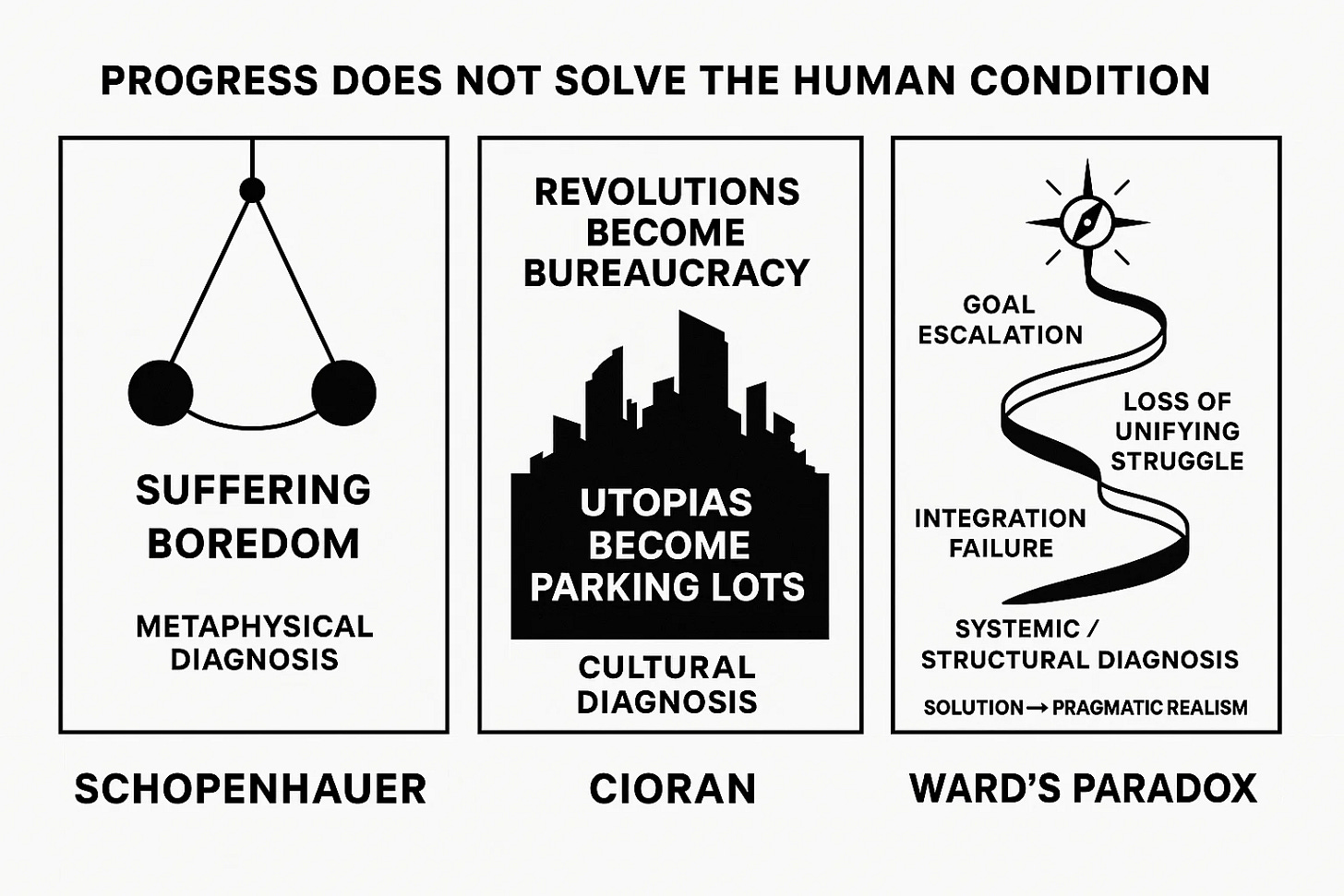

The Overlap and the Departure

All three frameworks recognize the same uncomfortable truth: progress doesn't solve the problem of being human. We're still dissatisfied, just at higher resolution.

But here's where they diverge:

Schopenhauer says the problem is metaphysical — the will itself is the villain. Solution: transcend the will through contemplation or denial.

Cioran says the problem is cultural — civilization exhausts itself through its own success. Solution: there isn't one, but at least we can laugh about it.

Ward's Paradox says the problem is structural — specific, identifiable mechanisms create predictable dissatisfaction patterns. Solution: conscious integration over unconscious accumulation.

Each thinker names the same problem but frames it differently. Schopenhauer saw suffering as metaphysical — the will itself was the villain — and his solution was withdrawal or transcendence, a grim determination to escape desire. Cioran read the problem as cultural — civilization exhausting itself through its own successes — and offered no solution beyond sardonic recognition. Ward’s Paradox reframes the problem as structural: success creates new failure modes through identifiable mechanisms. Its solution is not withdrawal or resignation but conscious integration over unconscious accumulation, a pragmatic realism fit for modern life.

Why This Matters Right Now

Ward's Paradox isn't just another philosophical framework to add to your cocktail party repertoire. It's a diagnosis for distinctly modern problems:

Information overload isn't about too much data — it's about goal escalation in knowledge acquisition. Every answer creates three new questions. Every article you read adds five to your backlog.

Institutional mission creep isn't about bad management — it's about integration failure. Universities optimize for rankings while education suffers. Hospitals optimize for billing while healing suffers.

Burnout culture isn't about working too hard — it's about loss of unifying struggle. We're exhausted not from effort but from effort without collective meaning. Everyone's climbing their own mountain, wondering why the view feels empty.

The framework explains why Silicon Valley billionaires end up depressed, why social media makes us lonelier, why having infinite entertainment options makes Sunday afternoon feel existentially heavy.

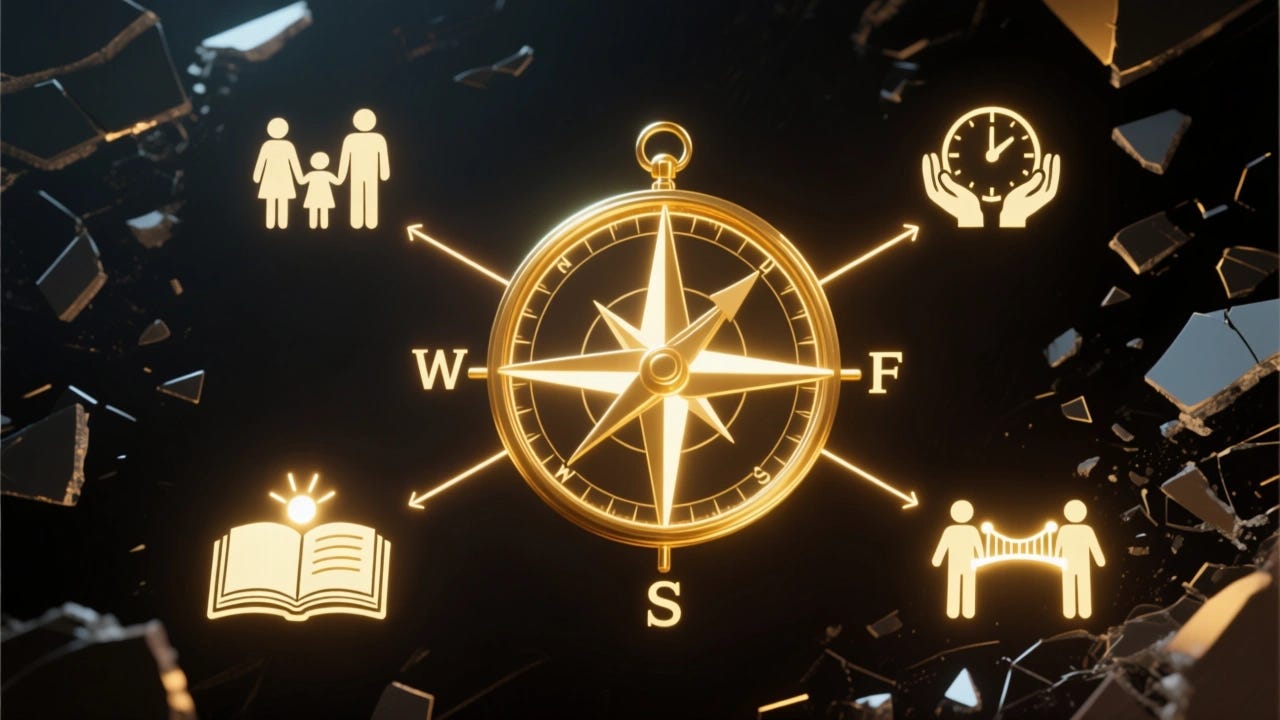

The Compass Principle: A Different Direction

Here's what Schopenhauer and Cioran missed: you don't have to opt out or give up.

The Compass principle suggests integration over accumulation. Instead of adding more (goal escalation), integrate what you have. Instead of optimizing parts (integration failure), optimize wholes. Instead of manufacturing struggle (loss of unifying struggle), find meaning in maintenance.

This isn't about lowering standards or embracing mediocrity. It's about recognizing that ten integrated life elements beat a hundred fragmented achievements.

A integrated life might look like:

Career success that enhances rather than replaces relationships

Wealth that buys time rather than obligations

Knowledge that creates wisdom rather than anxiety

Technology that connects rather than fragments

The paradox only wins if you play by its rules. Change the game from accumulation to integration, and suddenly progress serves rather than enslaves.

The Invitation

Schopenhauer would tell you to contemplate art until the will dissolves. Cioran would offer you a cigarette and a sardonic smile. Ward's Paradox suggests something different: understand the mechanism, then redesign your response.

You're not broken for feeling dissatisfied despite having everything. You're experiencing a predictable system output. The mall at 3 AM isn't your failure — it's what happens when we build cathedrals to consumption without asking what we're consuming for.

The question isn't whether you'll experience Ward's Paradox — you will, repeatedly, in every domain. The question is whether you'll recognize it when it happens and choose integration over the next escalation.

If you've ever achieved a major goal only to feel strangely empty afterward — you've lived this paradox. Subscribe to explore more patterns hiding in plain sight, or share this with someone still wondering why their promotion didn't fix everything.

Join the conversation → What domain of your life most needs integration over accumulation right now? If you got this far, thank you! The first 25 subscribers will get 1 month free premium access. Subscribe today!